Cheers for PEERS! Improved neural sensitivity to rewards in teens with autism spectrum disorder after intervention

By Elizabeth Baker, PhD Student (UCR Department of Education, Social Cognitive Developmental Neuroscience Lab)

Missing your family, friends, and social gatherings during quarantine? If so, it’s likely because you find social interaction to be rewarding. For some individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), this might not be the case according to the Social Motivation Hypothesis. ASD is characterized by challenges with social communication and the presence of repetitive and/or restricted behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The Social Motivation Hypothesis (Chevallier et al., 2012) seeks to describe why people with ASD might not find social interactions to be as rewarding as their neurotypical (TD) peers.

Social difficulties in ASD begin as early as infancy, with reduced attention paid to social images, and are present throughout development, making it harder to socially engage and maintain friendships later in life. The Social Cognitive Developmental Neuroscience Lab (SCDN Lab; PI: Dr. Katherine Stavropoulos) wondered if strengthening social skills would (a) help teens with ASD make friends and (b) enhance neural response to rewards.

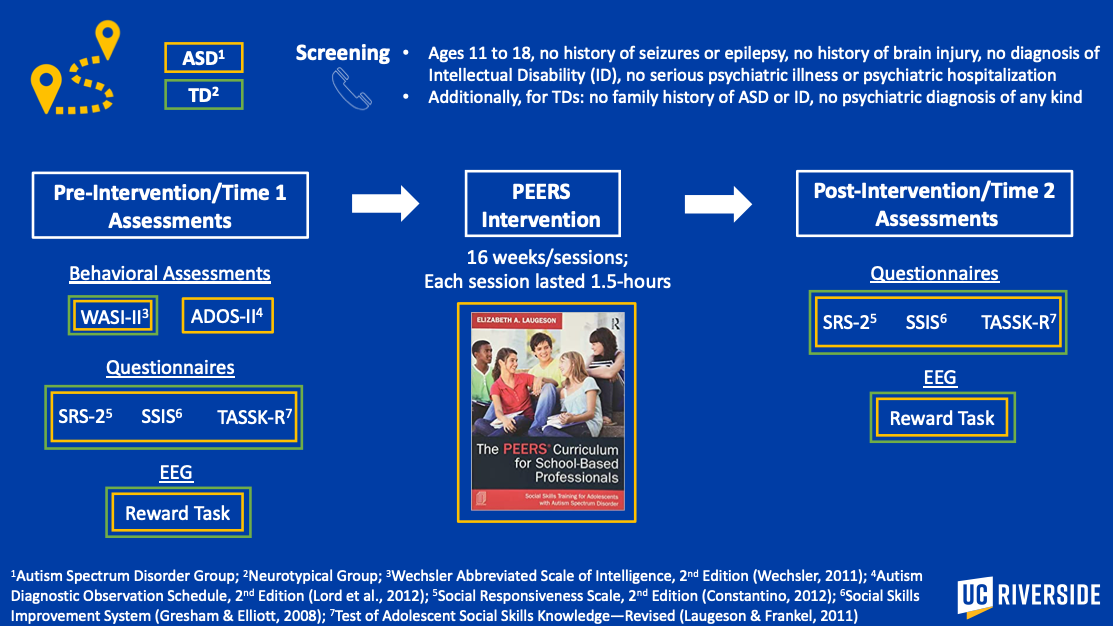

To answer these questions, we recruited a group of neurotypical (TD) adolescents and a group of adolescents with ASD. There were seven teens in each group, all of whom had average cognitive abilities and were about 13.5 years old. We used assessments and questionnaires to learn about their social behaviors. All the teens completed an EEG task to measure reward-related brain activity, particularly in response to social and nonsocial rewards.

After the initial visit to the SCDN Lab, the ASD group and their parents participated in a 16-week social skills intervention called PEERS, a group intervention designed to help adolescents make and keep friends (Laugeson, 2013; Laugeson et al., 2015; Laugeson & Frankel, 2011). Teens and parents met in separate rooms for 16 sessions, each session lasted 1.5 hours, and were led by trained interventionists. Some of the skills learned in PEERS include: texting dos & don’ts, how to identify qualities of a friend, how to start a conversation, and how to organize get-togethers. To accommodate a bilingual and predominantly Latinx sample from the Inland Empire, the parent group was run in both English and Spanish. After the intervention for the ASD group, and 16 weeks later (without intervention) for the TD group, we re-assessed social behaviors and the teens completed the same EEG task again.

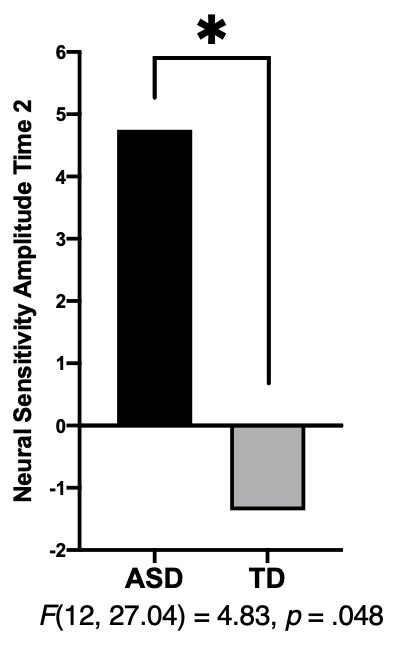

At the initial visit, the ASD group had more challenges with social behaviors compared the TD group, as expected given the social communication difficulties associated with ASD. Interestingly, both groups displayed similar brain activity in response to rewards before the ASD group began intervention. However, after intervention the ASD group had increased brain activity in response to rewarding stimuli compared to the TD group. This means that the PEERS intervention improved the ASD group’s response to both social and nonsocial rewards. When measuring the relationship between brain and behavior, we found that teens with ASD who had a smaller reward response to faces before intervention made the most gains in social skills after the PEERS intervention.

These findings are quite useful! First, they provide objective evidence that participation in PEERS causes measurable changes in brain activity for teens with ASD. Second, our findings show that PEERS might be the most effective for teens with ASD who have the most room to grow in terms of their response to social information. Third, this is one of the first studies to examine neural measures of reward response before and after intervention in a predominantly Latinx ASD sample—a group that is traditionally under-represented in EEG research. Finally, this suggests that the brain’s reward may be somewhat malleable, as our findings indicate teens with ASD who learn social skills get better at interacting with others and may therefore find such interactions more rewarding.

Findings reported in this blog are based on the following publication:

Baker, E., Veytsman, E., Martin, A. M., Blacher, J., & Stavropoulos, K. K. (2020). Increased neural reward responsivity in adolescents with ASD after social skills intervention. Brain Sciences, 10(6), 402.